The London Storyteller

Sadlers Wells, London. Thursday 10th July.

The presentation of Quadrophenia as a ballet is the most successful thematic realisation of the original concept as a marriage between music and visual expression. It is a powerful work of storytelling that reinterprets the rock opera through performative dance and a mostly classical instrumental score that elevates it to new heights.

Comparisons to the 1979 Franc Roddam film are inevitable but feel misguided. That film was good but flawed and had little to do with the original concept that underpinned Quadrophenia.

Justifiably it is considered the definitive portrayal of the Mod sub-culture movement on the silver screen but it was more a nostalgic advert for a dysfunctional lifestyle brand than the evocative cinematic presentation that The Who’s 1973 song cycle deserved.

In the same way that Michael Caine’s tragic anti-hero Alfie became an aspirational figure for would be lotharios, some audiences have been happy to take the sizzle and leave the sausage on the plate. It is perhaps iconic because we have been told it is in the years since it was released.

The original album’s success as a conceptual work was rooted in it being a prop to the imagination and the ballet flows strongly along this more emotive vein of artistic expression.

Returning the story to it’s original frame, the ballet goes back to central image described in the prologue of the original album: a lost soul stranded on a rock experiencing an existential spiritual crisis.

Quadrophenia was always for me this first and a social document of the post-war 1960s setting in which it is set second. The notion that humanity shares an existence of clinging onto earth amidst a universal sea. This ballet production realises this with majesty and innovation.

In this sense, the ballet is a considerable triumph. It restores Quadrophenia to it’s true function and that which has elevated Townshend’s writing over the years to it’s most transcendent power.

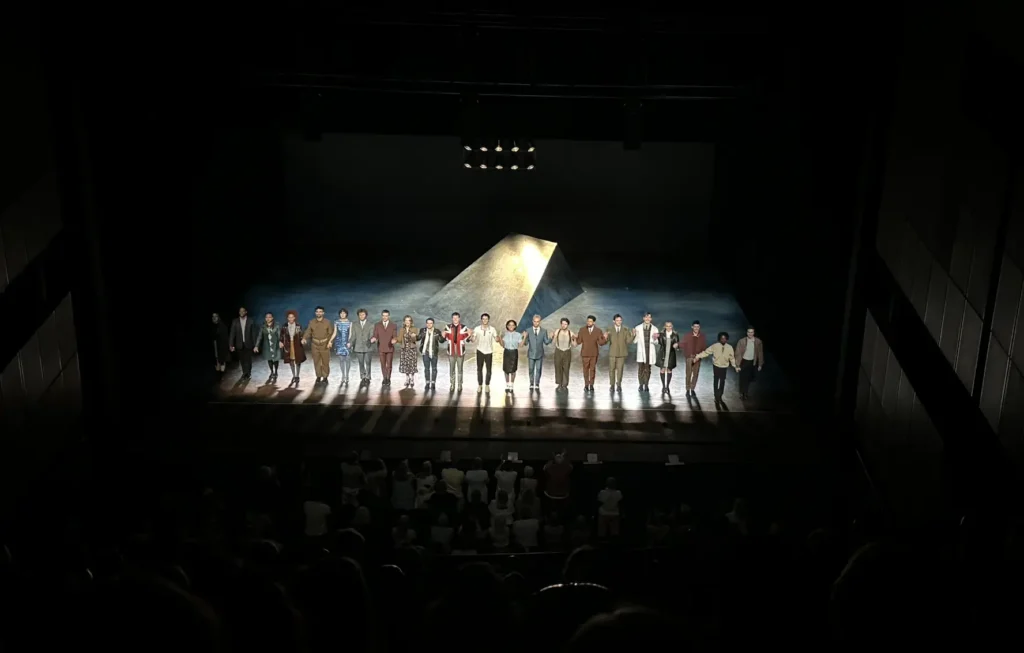

Visually it stuns with a combination of technology and choreography by exploring a path that Quadrophenia has always offered but that has never quite been pursued successfully. A series of images, dreams and fragmented recollections; the marriage of music with performative art. Sitting up in the gods of Sadler’s Wells, I looked down upon a river of passing scenes, time and characters along which the story flowed as though projected by some kind of celestial camera obscura.

I read in one review that this was a production set up for “rock fans looking for a good time”. This is a colossally cretinous and casual misrepresentation of what the Quadrophenia ballet is and what it achieves.

The Who’s canon has long contained within it the capacity to straddle the boundary between popular culture and the classical arts. The ballet demonstrates this better than I think anything else that has been done with that body of work in this respect.

It is a work of art in truest sense in that great art transports its audience. Nonetheless. there is plenty of meat on the bones of the social document of it’s setting that hits home too.

One especially emotive scene explores the war time story of Jimmy’s father. I once crossed the forbidden line of asking my grandfather about his to which I was given a very succinct reply and I never dared to venture to subject again. What he told me is not something that you want to know. His son, my father, resplendent in his Korean war army parka jacket was at the so called battles of Clacton, Hastings and Brighton as a Mod. He recalls this as jolly japes, winding up Rockers and then making fast his escape on a Lambretta on the occasions that it started. Therein lies the crux of the generation gap the social experience of the boomer generation for many and how a generation of men became emotionally unapproachable.

At the heart of the production is the collaboration between the work’s original composer, Pete Townshend, and his wife Rachel Fuller who orchestrated and arranged the classical interpretation released a decade ago. This partnership began with the realisation of BBC Lifehouse radio play in 1999 and has matured over the last quarter century.

I enjoyed but didn’t feel that Classic Quadrophenia took me anywhere that the original album hadn’t already. What is clear now is how that the real value of that process is validated; as it provides the foundation from which the ballet has been built. There are moments of contemplative sensitivity contrasted with awesome power unleashed from Townshend’s original score and realised by Fuller’s oversight.

This setting allows much new and compelling substance to emerge in the absence of lyrics and considering the brilliance of Townshend’s skill as a lyricist this is no small feat. Music is after all a universal language and at central to Quadrophenia are universal themes.

This production is an important moment in Who history and if it is an outlier for what how the legacy of Townshend’s body of work may evolve in the years that come, this is to be looked forward to with optimism. I have previously pondered whether the lost Lifehouse project may finally be realised as an animated film but can see now that there is perhaps a more ambitious and apposite form to finally bring this home which the Quadrophenia ballet may have laid the path for.

My most reliable marker for knowing when something I have experienced has worked as art, is that it tends to transfer or create in me a force of creative energy, enthusiasm and purpose. A sense perhaps that stars may align and perhaps after all there is some kind of spiritual alchemy is at play. Walking out of Sadler’s Wells and into the baking Islington summer sun, I carried precisely this with me and onward.

The London Storyteller is proudly powered by WordPress